Digital Access in Indonesia—A Luxury for Learning in a Time of Pandemic

by Dio Suhenda

Close to 70 million students from preschool to university in Indonesia are now forced to continue their academic endeavors at home, as schools across the country are forced to close (World Bank, 2020). However, online education is dominated by a single prerequisite—digital access. Unfortunately, this remains a luxury many cannot attain, rather than a public good afforded to all.

With online learning now in full swing across the country, many parents have put their profession on the backseat, either because of the pandemic, or in order to assist their child’s new form of education.

One such parent is Nova Meuthia, who lives in Depok, a suburb of Jakarta, the capital. A single mother of four, Nova had previously provided for her family by working as a professional tailor. However, Nova now grapples with the economic brunt that has resulted from the pandemic and its consequent online learning for school children, through mobile phones, laptops and internet data.

“Before the pandemic, I would usually go to my clients in their offices to tailor uniforms. But now, I spend more time with my children, leaving little time for me to earn my income. Any time I spend working, I have to do it while teaching them,” said Nova, in August this year.

As a result of her economic circumstances, Nova now shares one mobile phone between herself, her youngest child and second youngest child, in the first and fourth grade of elementary school, respectively. In between her children’s online classroom sessions and Youtube video assignments, Nova has little time to communicate with her clients, often having to wrestle her phone away from her children.

Her dream now is to buy a laptop for her children’s education. However, with no end to the pandemic in sight, she currently communicates with her clients only through her mobile phone.

On the other hand, 51-year-old kindergarten principal, Miss Valen, offers an acute insight to how schools are handling this problem. Having been a teacher since 1989, Miss Valen now heads a private Catholic kindergarten in the Bintaro, a suburb of Jakarta.

In her kindergarten, Miss Valen prepares a range of activities for her students. “In each household, a family may have more than one child who needs the same device, such as a laptop or an Android phone. So, as a school, we have to do a survey, and adjust with the parents. Thankfully, we are able to coordinate,” Valen said.

The School Under the Bridge

A person who has seen her fair share of students losing the fight against online learning is Early Childhood Year (ECY) education specialist, Valentina Sastrodihardjo.

“In Jakarta, we already see a lot of parents protesting [about online learning]. What about the more rural areas? The ones who would have to climb up a mountain just to get some signal. At the end of the day, from a psychological perspective, the children will give up more easily,” said Valentina, in August this year.

Valentina refuses to give up on the betterment of children through education, and is now taking matters into her own hands. As of late, she busies herself with ‘Rumah Belajar Pelangi Nusantara,’ (the Nusantara Rainbow Learning Home), the community education center she founded.

Valentina has never lost sight of her vision to teach basic arithmetic to the children of Jakarta’s garbage collectors, who are concentrated in the Rawamangun area. She initially had more than 150 students. However, since the forced eviction of garbage collectors living in the shanty towns of Rawamangun, that number has been reduced to sixty.

Her centre is now located under a bridge in Rawamangun, one of the capital’s most underserved districts. Having initially conducted lessons in the homes of willing parents, in 2015, changing circumstances of these parents’ living situations eventually forced her to set up her community education centre in a place where eviction would not be a problem—under the bridge.

However, the pandemic has hit especially hard for her students and their families.

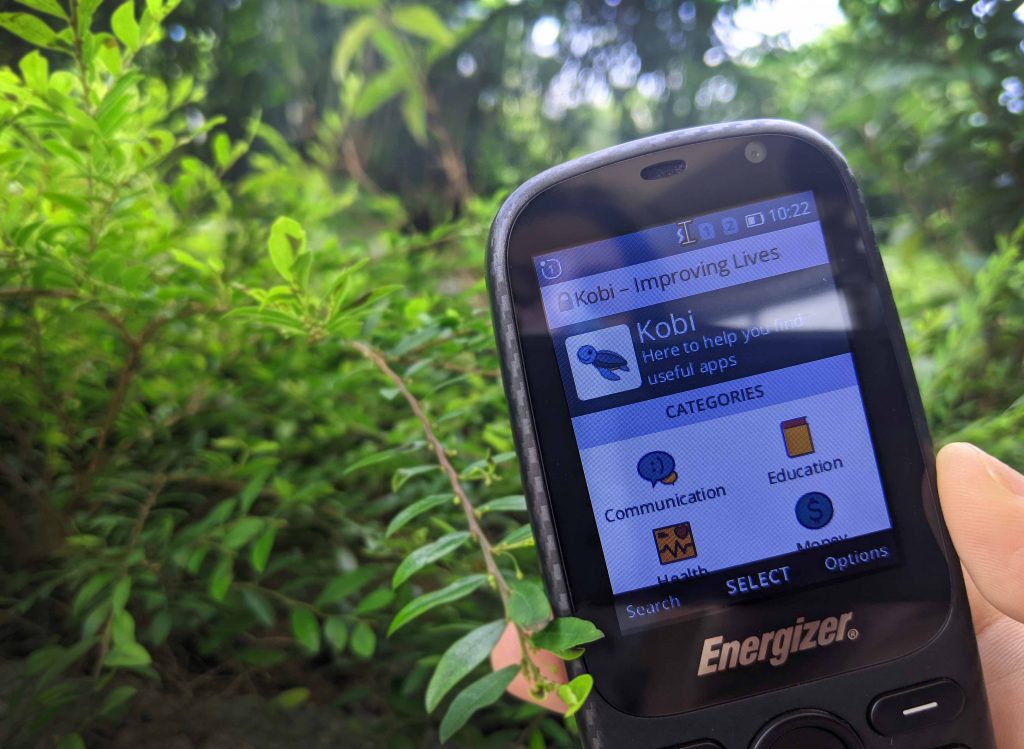

“There is no government support. For these kids, from what I can see, their phones do not support Zoom or Google Classroom. In less than a minute of being turned on, the phones crash. Secondly, their parents are clueless (about technology). They are cleaning laborers,” says Valentina, of the problems her students are facing.

In particular, Valentina cannot help but be concerned about one of her students, third grader Alif. Valentina recollects how Alif was always eager to learn, attending her classes every weekend. Sadly, Alif lives in a 2- by 3-meter home with his factory laborer mother, and his father, who has recently lost his job as a driver to the pandemic. Alif’s father now scrapes by an income standing guard for a fishing pond.

Valentina was helpless watching her students struggling without the necessary digital access for online learning. Fortunately for Valentina, a group of journalists had banded together in March 2020 to form Wartawan Lintas Media (Cross Media Journalists). They are committed to “being an instrument for the community to help each other and to seek help,” as described by founding member, Ghina Galiya, in an interview in August. These journalists were quick to respond to Valentina’s appeals for help.

“They (the less fortunate and casual workers in Indonesia) had lost their income even before the PSBB (Large Scale Social Restriction policy) as the streets were empty, people were staying at home. We, as journalists who monitor the policymaking process daily as part of our jobs, felt that it wasn’t right to stay behind the desk in such situations,” said Ghina.

Having received donations of mobile phones from across the country, Wartawan Lintas Media is distributing it to several underserved areas in the capital Jakarta, such as Valentina’s kids in Rawamangun, while also shipping it to students outside the capital.

In order to ascertain that the donated phones do not fall into the wrong hands, Wartawan Lintas Media requires students applying for them to submit a copy of their report card and to complete an assignment, usually in the form of an essay.

“We’ve received at least 70-ish submissions from students. We select those whose families have only one phone or have two phones but with many family members,” Ghina said.

Interestingly, Wartawan Lintas Media did not start by focusing on phone donations. After previously running a handful of charity campaigns raising funds for basic needs, the group, noticed the pandemic had unearthed another problem many were oblivious to—the essential commodity that is the mobile phone.

““In Jakarta, we already see a lot of parents protesting [about online learning]. What about the more rural areas? The ones who would have to climb up a mountain just to get some signal. At the end of the day, from a psychological perspective, the children will give up more easily.”

—Valentina Sastrodihardjo, founder of community education center, Rumah Belajar Pelangi Nusantara (Nusantara Rainbow Learning Home)

Digital Infrastructure and the Digital Divide

A 2019 survey by the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), indicated that only 31.64 percent of students belonging to the lowest quintile of Indonesian households have access to the internet, while 78.73 percent of students belonging to the top quintile of Indonesian households enjoy access to the internet.

“I think the current main problem is the internet penetration disparity that has yet to benefit the majority of the population. Access to the internet is still expensive for the poor although our (the Indonesian) digital infrastructure, such as electricity and cellular signals, has been deemed adequate,” said Ghina.

A 2019 survey by the Central Statistics Agency (BPS), indicated that only 31.64 percent of students belonging to the lowest quintile of Indonesian households have access to the internet, while 78.73 percent of students belonging to the top quintile of Indonesian households enjoy access to the internet.

“I think the current main problem is the internet penetration disparity that has yet to benefit the majority of the population. Access to the internet is still expensive for the poor although our (the Indonesian) digital infrastructure, such as electricity and cellular signals, has been deemed adequate,” said Ghina.

In context, despite a majority 66.22 percent of villages throughout Indonesia having good access to the internet (the Ministry of Information and Communication Technology, 2018), only 29.56 percent of active Indonesian students accessed the internet at least once, over a period of three months in the year 2018, (BPS, 2018).

Although poor internet connection is nevertheless a problem of the digital divide, the case here might truly boil down to the unattainability of internet’s prerequisites—internet data and a mobile phone.

To put it into perspective, although 88.46 percent of Indonesia’s households have access to a mobile device, the national average suggests that only 2.46 members of a household owns a mobile phone. In contrast, the national average shows that an Indonesian household in 2019 has 3.9 family members. With cell phone ownership mainly being claimed by parents, children remain starved of internet access.

“It has been the country’s problem for years and has therefore affected the people in times like this,” commented Ghina, when asked about Indonesia’s deep rooted digital divide problem.

If left unchecked, the inability to access online learning might create a systemic division between students from the low and the high income groups, as the digital divide cripples education into a contest of social capital.

Valentina however, can now rest easy. Twelve of her kids from Rumah Belajar Pelangi Nusantara have now received donations of mobile phones they can finally use for online learning, thanks to the charitable work of Wartawan Lintas Media.

The kids of Rumah Belajar Pelangi Nusantara have had their glimmer of hope reignited, thanks to Valentina and Wartawan Lintas Media. Although the sun beyond the horizon is yet to be seen, they can now better navigate the global pandemic.

Dio Suhenda is a journalist from Indonesia with a keen interest in education and culture, who fancies himself a teacher. He used to be obsessed with the idea of being a catalyst. Now, he is more than happy to precipitate his writing as educational currency, as he believes knowledge to have value only when shared. He sees the problems in the world as stories yet untold, for the journalist to learn from and educate the world about.

Our latest posts

Digital divide in Thailand and Timor-Leste’s rural population

How economic policies in the US and China affect the digitally underserved

What does the digital divide around the world look like? In the second post in this series on the barriers to internet access, SpudnikLab explores digitally marginalised groups caught in the deep-rooted rivalry between two economic giants.

Why SpudnikLab Loves Citizen Science

April is Citizen Science Month! We wax lyrical about why these 30 days dedicated to works of science by ordinary folk around the world rock our world.