How a Free App is Lowering Farmer Suicide Rates in India

by Krishna Deep

It is the oldest story in the book. Farmer wakes up. Farmer faces trouble. Farmer kills himself.

The other farmers stage protests, demand things from the system, realise they cannot afford to do it for too long, then go back to their lives.

The statistics around the number of farmer suicides in India are hard to understand, because deaths are not reported accurately. The primary reason why suicides are not reported accurately in India is because of the smear of “family shame” it carries.

Despite these social complexities, the known numbers stand at about 30 farmer suicides per day.[1] India’s Ministry of Home Affairs confirmed in November 2019, through the country’s National Crime Records Bureau’s accidental deaths and suicides report, that 11,379 farmers died by suicide in India in 2016. This works out to 948 suicides every month, or 31 suicides every day.[2]

That may not seem like much for a country of over 1.3 billion, but it’s a collective shame that the people working to feed their country have to resort to killing themselves as a way out.

[1] https://thewire.in/agriculture/farmer-suicides-data

[2] https://thewire.in/agriculture/farmer-suicides-data

The Wake Up Call

It was a lazy winter afternoon in 2016 in Southern India when Naveen Kumar received a jolt. A typical yuppie blissfully unaware of life outside of city comforts, Naveen was returning to his hometown—a quiet, quaint village a two-hour drive from the city of Hyderabad. As his bike negotiated the inner roads of the village, he saw a group of people huddled together in a field on the side of the road. Curious, he parked and approached the field. Lying in the field was the dead body of a farmer. He found out later that the farmer had been cheated by the local seed shop dealer, who had sold him fake cotton seeds. These seeds germinated into crops that didn’t produce yield. From the duplicity, the shop owner earned a profit of INR.300 (USD4).

Naveen felt deeply uncomfortable that all this was happening in his own village. He decided to do something about it. But what? He was just like any other banking professional with a job in the big city. How could he take on the mammoth system and its flaws? He figured he could at least try to understand the questions better.

For the next three months, Naveen travelled within his village and to other villages, to meet farmers of all social and economic status. He asked them what their challenges were in agriculture, and what drove some of them to suicide. He also visited shopkeepers to understand what would prompt these underhand transactions.

Naveen found there are close to twenty factors a farmer has to grapple with, such as seeds, weeding, pesticides and fertilizer, weather and rainfall, warehousing and processing units, electricity and water supply and market links. Every human factor is susceptible to human corruption. Every natural factor involves a game of chance.

Naveen also found that the human factors were actually well-researched and documented by ICAR (Indian Council for Agricultural Research) and many other institutions, such as universities.At the end of his instinctive research, Naveen realised the challenges the farmers faced could be solved using his network as an IT professional with HDFC bank, one of the biggest corporate banks in India. But he still didn’t have a vision for how he would go about accomplishing this.

Some time later, one of the farmers he had met with called him to ask him about a pest he was having trouble with. The farmer had saved Naveen’s number in his phone, thinking he was a government agricultural officer. Farmers are used to people from cities turning up and asking them all sorts of questions, and such people are often agricultural officers. Naveen did a quick google of the farmer’s question, then gave him the answer over the phone. He learned a few days later that the solution had worked. That was the eureka moment. Naveen decided he would design an app that would help farmers get access to information quickly, and for free.

Although he knew very little about building apps, being in the IT industry gave him an advantage. He found two friends who were willing to help him build an app. Thus, ‘NaPanta’ was born. Naveen quit his job and started following the true north of his moral compass.

An App is Born

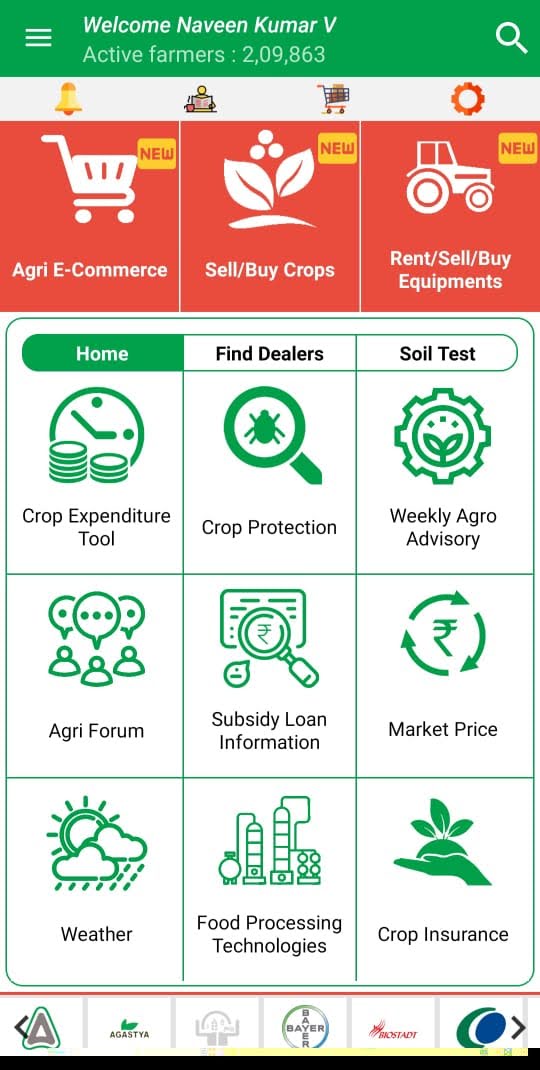

‘NaPanta’ translates to ‘My Harvest’ in Telugu. The team found a way to break down and organise multiple sources of widely and freely available valuable information on sixteen critical agricultural factors from researchers and scientists, and distribute it to farmers within seconds.

NaPanta, like all apps, was a trial and error exercise for the development team (https://www.napanta.com/napanta-team.html). However, their most basic version still hit 50,000 downloads within the first three months of its launch in June 2017. But soon, farmers were uninstalling the app because it too heavy (more than 50MB) and complex to use. They spent the next three months finetuning the app—removing data-heavy features, adding more valuable and easy to use features such as a crop expenditure tool and information on local weather, and reduced the size of the app to under 7MB, with operating space of about 40MB required. All these made the app easy to install and use. NaPanta spent no money on advertising or marketing. Farmers across the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh started downloading and sharing the app like wildfire.

‘Farming is a job, a business, a lifestyle, a duty, all rolled into one,” he says. “In the midst of all this, we have to face a lot of problems, most of which have to do with understanding how crop cycles and pests work. Because we may work for five months but the yield could be gone in a few hours if we neglect the pests.”

—Madhu, a farmer in the Jogulamba Gajwel district of Telangana state, India.

Teething Problems

‘NaPanta’ translates to ‘My Harvest’ in Telugu. The team has found a way to break down and organise multiple sources of widely and freely available valuable information on 16 critical agricultural factors from researchers and scientists, and distribute it to farmers within seconds.

NaPanta, like all apps, was a trial and error exercise for the development team (https://www.napanta.com/napanta-team.html). However, their most basic version still hit 50,000 downloads within the first three months of its launch in June 2017. But soon, farmers were uninstalling the app because it too heavy (more than 50MB) and and complex to use. So they spent the next three months finetuning the app—removing data-heavy features, adding more valuable and easy to use features such as a crop expenditure tool and information on local weather, and reduced the size of the app to under 7MB, with operating space of about 40MB required. All these made the app easy to install and use. This ended being the tipping point they were looking for. NaPanta spent no money on advertising or marketing the app. Still, such was the value it added to farmers’ lives, farmers across the states of Telangana and Andhra Pradesh started downloading and sharing the app like wildfire.

Simple Isn’t Always Easy

Madhu (last name protected on request) is like any other farmer in the district of Jogulamba Gajwel in the state of Telangana. He grows cotton, rice, sugarcane and some pulses. Madhu is one of the few educated farmers in the state. Having inherited 3 acres of land, he rents another 10 acres. Whatever money he can earn from these 13 acres is his financial security. “Farming is a job, a business, a lifestyle, a duty, all rolled into one,” he says. “In the midst of all this, we have to face a lot of problems, most of which have to do with understanding how crop cycles and pests work. Because we may work for five months but the yield could be gone in a few hours if we neglect the pests. The information about how to deal with pests is very valuable.”

He went on to explain how NaPanta helped him understand the problems he was facing, and also to help him foresee problems that he might end up having with pests. Madhu also relies on the ‘sell/buy crops’ feature of the app to get a bird’s eye view of how prices change in the market. Though that is his favourite feature, he also uses the features about weather, weekly agro advisory and crop insurance. In the last year, he achieved complete optimisation of his farm land by understanding the market prices and planning for the yield ahead of time.

Madhu is one of the millions of farmers who have benefited from India’s strong mobile infrastructure. Although broadband internet connectivity is still a dream in most villages, including Madhu’s, the 3G connection on his phone suffices for using the app. Most cell phone subscribers provide 1GB of free data per day for a very affordable monthly fee (between Rs.100–300 or USD1.30–4.00).

Providing Solutions, Saving Lives

Madhu testified to his profits increasing with help from the app. He also mentioned how the app, as well as other factors, including state and central interventions, have successfully brought down the collective anxiety of farmers. According to him, the suicide rates in their district went down by at least 50 percent in the last two years. Though there is no direct way of verifying this claim, the national average does show a decline of 10 percent over the last three years.[3]

At the time of writing this article in August 2020, around 210,000 farmers are registered on NaPanta. They benefit from services such as subsidy loan information, market prices, crop protection information, crop insurance and expenditure tools, and a forum with more than 10,000 and counting question-answer threads. The app currently serves two states, with services in English and Telugu. The team plans to expand its reach to 17 states by adding four more languages and is in the process of negotiating MoUs with different state governments. NaPanta is doing its part in helping save lives and crops on the ground with technology in the cloud, one app download at a time.

[3] https://indianexpress.com/article/india/steady-decline-in-farm-sector-suicides-from-2016-to-2019-ncrb-data-shows-6580833/